This is one of those blog posts in which I demonstrate the nitty-gritty of research in an aggravatingly nit-picky way.

This is an amended reboot from 2012 when I first started writing Prudence.

Read at your own risk.

To protect the guilty I’m not going to name any names, Gentle Reader, and I’d like to state up front that currency is not my expertise.

However, I was reading a book of the alt-historical romantic variety. The hero visits a whore in Victorian London, 1883.

For her pains he “pulled out far more notes than planned and handed them to her.”

I had to put the book down.

It was very upsetting.

Coins vs. Notes in Victorian England

BANK NOTES!

First, bank notes are drawn on a bank more like a cashier’s check (or an IOU) than paper money today, which means the whore in our above example would have to go into a bank to redeem her notes or find herself a very non-suspicious tradesman, in modern times this is a little like trying to break a $1000 bill.

ON YOUR PERSON?

Second, no one regularly carried notes or paid for anything with notes until well after the 1920s. Culturally, no one would carry that much money into the kind of area of London where whore houses are located.

For services people paid with coin, with tradesmen (who handle goods) the wealthy actually paid via their butler or valet or abigail’s coin, or on account, because it was beneath them to physically touch money.

Even, as the author was trying to get across, this was a highly generous gesture, NOT WITH PAPER MONEY HE WOULDN’T.

*HEAVY BREATHING*

We writers all make mistakes. I have made more than my share. And there comes a time when every historical author must stop researching and begin writing (or the book never gets written).

I do understand and believe that some modernization is necessary in alt-history genre fiction because most readers want their books to be fun and entertaining. It is our business, as authors, to provide that first. (Now for genres like historical fiction or biographies this is a different matter. I am speaking in terms of managing expectations.)

BUT IT’S MONEY

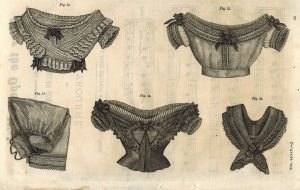

However, I do think something as basic as currency should be second knowledge if you are going to write in any alternate time period. It’s like getting the basic clothing terms correct. (In another unnamed steampunk novel, a corset was referred to as a bodice. FYI, both terms are incorrect. At the time, a corset would have been mainly referred to as stays. The bodice is the top part of a dress. Thus, I spent the entire scene confused into thinking the character in question was swanning around with only her torso dressed, rather than entirely in her underthings as was intended. But, I digress . . .)

Godeys July 1872 Bodices

On Victorian Money (from Baedecker’s London 1896)

- sovereign or pound (gold) = 20 shillings

- half-sovereign (gold) = 10 shillings

- crown (silver) = 5 shillings

- half-crown (silver) = (2 shillings & a six penny piece)

- double florin (silver – rare) = 4 shillings

- florin (silver) = 2 shillings

- shilling (silver & same size as a sovereign) = 12 pennies

- six penny (silver) = 6 pennies

- three penny (silver) = 3 pennies

- penny (bronze) = 4 farthings

- half penny = 2 farthings

- farthing

|

| From lot at auction. |

I know, I know, overly complicated. Think back to that wonderful scene with the money exchange in Room With a View when Cousin Charlotte comes to visit Lucy’s family.

“In England alone of the more important states of Europe the currency is arranged without reference to the decimal system.”

~ Karl Baedeker, 1896

Victorian Money in Terms of Value

In 1896: 1 sovereign was approximately: 5 American dollars, 25 francs, 20 German marks, or 10 Austrian florins.

To reiterate: The Bank of England issued notes for 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 pounds or more. They were generally not used in ordinary life as most people “dealt in coin.” Gentlemen and ladies, when shopping, either had a servant with them to handle the coin (including gratuities & all fares) or paid on credit (AKA account). A shop would then send a bill around to the townhouse at the end of the month on Black Monday, which would be paid by the house steward, accountant, or personal secretary. A gentleman handling his own money is either no gentleman or engaged in nefarious activities like gambling or trade.

Baedeker advises letters of credit (AKA circular notes) drawn on a major bank for travel, to be exchanged for local currency upon arrival. He also advises never carrying a full days worth of coinage about your person.

It’s important, as historical writers, for us to grasp a larger picture – so allow me to attempt to put this into perspective…

Middle class wages per annum 1850-1890:

- A Bank of England Clerk £75 to £500

- Civil Service clerk £80 to £200

- Post Office clerk £90 to £260

- Senior Post Office clerk £350 to £500

So let’s say a middle class wage was anything from £75 to £500 a year, that’s £1.44 – £9.61 a week for a relatively comfortable lifestyle.

Since there is no £1 note, to “pull out far more notes than planned” as our unnamed author writes above, and give such to a whore, means at least £5 per note. More than one means at least £10. Not only should this character not have been carrying that kind of money, he just tipped that woman better than one week’s salary for the upper middle class to someone who likely could never break that bill, today that’s something on the order of $2,500.

A gentleman of lower standing, say a younger son with a Living could expect something similar to upper middle class £350-500.

Titled or large landed gentry could pull in anything from £1000 to £10,000 a year (what, you thought the 99% was a new thing?).

A dowry for landed country gentry’s daughter of few means would be about £100 a year.

Still, even the highest aristocrat wouldn’t tip in notes, ever. If for no other reason than it’s the kind of thing the neuvo riche, or An American might do. (It’s worth noting that poor were a great deal poorer, earning shillings per week or less.)

Later on, this same author writes “cost me twenty quid to delay matters” of bribing a coroner to delay a funeral. That’s a heavy bribe, about $5000. I couldn’t find any information on coroner’s pay in Victorian times (the job was either uncommon, not yet official, or went by another name) so let’s say grave digger, which is well below middle class, so a £20 bribe would probably be about a year’s income for the man.

End of Rant

A Budget from 19th Century Historical Tidbits

Sorry, I just had to get that off my chest. Or should I say “out of my chest”? Chink chink.

So, if you have a Victorian setting (really, anything up through the 1920s) what do we pay with?

Yes, that’s right children, coins!

This is also a rather depressingly clear indication of how Gail Carriger spends her weekends. I am such a dork.

“I may be a chump, but it’s my boast that I don’t owe a penny to a single soul – not counting tradesmen, of course.”

~ Carry On, Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

As always, you don’t have to take my word for it. Earlier in time, but still relevant podcast…

More or Less Behind the Stats: How Rich was Jane Austen’s Mr Darcy?

How does this relate to Prudence?

Well might you ask. What I had to do (or thought I had to do) was determine the conversion rate between pounds and rupees traveling from England to India in 1895.

Unfortunately, Baedecker didn’t write for India.

What I ended up having to do was make some very loose estimations based on the above assumptions of middle class wages and the information I could source, which was monthly accounts for a household of four living in India on a diplomat’s wage between 1880 and 1897 (something on the order of £500 per annum). Here’s my fun chart:

Here’s hoping the above was, if not fun, at least informative or, if you yourself are an author, helpful.

Prudence by Gail Carriger

Pip pip!

{Gail’s monthly read along for January 2016 is The Raven’s Ring by Patricia Wrede. You do not have to have read any other Lyra books.}

GAIL’S DAILY DOSE

Your Infusion of Cute . . .

Octopus Candle Holder

Your Tisane of Smart . . .

Knickerbockers for Women: From Under the Hiking Skirts to the Fad of the Hour

Your Writerly Tinctures . . .

“Writing my books I enjoy. It is the thinking them out that is apt to blot the sunshine from my life.”

~ P.G. Wodehouse

Book News:

Sam of ARC Review says of Manners & Mutiny:

“While I’m having a hard time letting these characters go, I won’t forget the mayhem they caused, and the joy they gave me as a reader.”

Quote of the Day:

“Da Silva announced his intention of settling in the library to commune with his muse. Curtis, feeling sorry for the muse, said that he preferred to explore the house and acquaint himself with its features.”

~ Think of England by KJ Charles

Tags: Beginning Writers, PRUDENCE, Steampunk, Victorian Culture, Victorian Science

yeah, first page of a book set in England early 1800s and a 5 year old compares her dad's hair to a porcupine, not a hedgehog. I ughed and nearly threw away the book.

A coroner in Victorian England? Unheard of.

A funeral furnisher or a funeral planner ran the actual funeral, but it was the job of midwives to lay out the body. Yep, I said midwives. The same women who brought you into the world also saw you on your way out.

Embalming wasn't terribly common if the body was meant to be buried within a few days of death. It was used more if the body was to be transported elsewhere for burial and the travel would be longer than a week.